How dangerous products hurt in more ways than one

To err is human, and this perhaps is the greatest justification for corporate personhood. Sometimes, mistakes are made and products are released with these mistakes. Using these products may cause harm, and therefore it becomes the moral and legal responsibility to remove these products from the market, and issue a recall.

Recalls are expensive. There is the cost of tracking down and informing consumers, the cost to manufacture replacements, and the liability lawsuits for damages caused by the faulty products. Beyond that, there is the reputational risk, and the negative association of a brand. According to Allianz, the average financial cost of a recall was ~$1.65 million (2017 USD), with a fat-tailed distribution meaning the cost can often go far beyond [1].

The real cost of recalls however, lies in the people hurt by them. Recalls almost universally fall far short of 100% success rates [2], and the harm that those for whom the message isn’t reached can be devastating, or even fatal.

The Healthcare Industry is the 6th most impacted by product recalls [1]

Whilst medical devices and pharmaceuticals have the fortunate position of being heavily monitored and tracked, so having recall effectivenesses far higher than their consumer goods counterparts, the potential for harm is so much greater, precisely because of their vulnerability and the need for them. It is a cruel case when the devices needed to save a patient’s life is what causes them harm. But the form this harm takes differs between device and drug.

Medical devices in the US are managed by the FDA. And they operate a 3-tiered classification system for recalls [3]. The most severe of these is Class 1. Here use of the faulty product is expected to cause death or permanent disability in over 50% of cases if used (the term used by the FDA is “Reasonable Chance”) [4]. The urgency of these recalls cannot be emphasized, as every delay to communication endangers the lives of many patients. Class 2 recalls are less severe, with the faulty product’s use expected to lead to temporary or medically reversible harm in the majority of exposures, and is considered unlikely to cause the sort of life-altering harm of their Class 1 counterparts. Class 3 is less severe still - with low expectations for any harm other than the superficial.

And with the use of devices being so acute to the patient, the dominant harm done to them by faulty products is from their use. This is the “simple” and intuitive model for how harm is done by the failure of product quality control and safety checks.

By comparison, whilst pharmaceuticals are similarly classified in recalls by the FDA, the reality is that (thankfully) most drugs are recalled before they reach consumers. And the typical reason for this is mislabeling or faulty storage and transport. Those drugs that are truly harmful to patients are instead withdrawn from the market. And these withdrawals, whilst infamous when they occur, are few and far between. This means that the real risk of direct harm to patients is considerably lower than for medical devices. Instead the route for the harm pharmaceuticals take is less direct, but far more widespread.

Pharmaceuticals and Pricing Dynamics

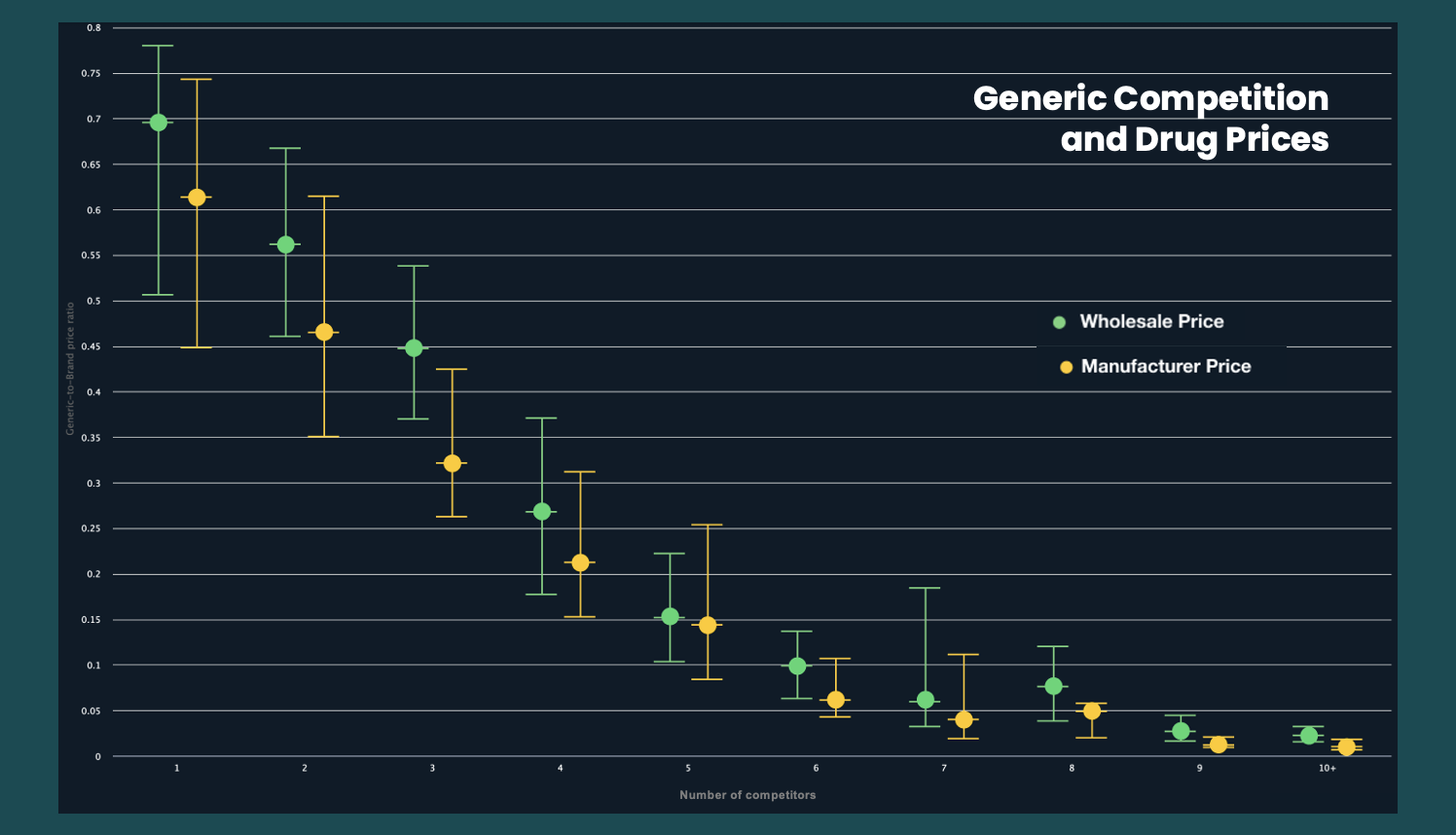

It is no secret that pharmaceutical companies operate with low competition. As such, the addition or removal of a single competitor in the market can have a significant impact on the price per dose. The addition of a single competitor in a previous drug monopoly leads to an average 31% decrease in wholesale price [5, 6].

Fig 1. The ratio between the price of a drug without competitors and with the number of additional competitors, measured with both wholesale price as well as in the average manufacturer price. Adapted from [5,6].

Because of the low-competitor nature of the pharmaceuticals industry, prices are incredibly sensitive to the number of competitors in the market. As such, even the temporary removal of a single competitor leads to a significant price increase for the pharmaceutical. Given the majority of drugs (over 60%) in the US market have 3 or fewer competitors, we can see that the drop from 2 generic producers to 1 leads to a price hike of over 20%.

It is this sudden price hike that hurts patients the most. In countries without a national health service such as the US, patients are at risk of being directly priced out from receiving the drugs they require to live. Making this an immediate accessibility concern in an industry already controversial for its unaffordability. In countries with a nationalized health care system such as the UK, whilst individual patients are shielded from the worst of these accessibility issues, the price hike instead hurts the ability for money to be invested elsewhere, gouging the budget for greater healthcare provision.

Fortunately, this price hike is contested soon after - the recalling company re-enters the market. But they re-enter at a higher price point, and it takes time therefore for competition to drive the price back down to the equilibrium price it was set at before the recall took place. Time that, for some of these pharmaceuticals and the patients taking them, is simply not available.

It is easy for us as people to fall into the trap that all harms are proportional. Our minds think linearly. But for us to accurately represent impacts, we must recognize that those models, whilst sometimes useful, are not universal. With recalls, we must go beyond social costs. In cases like medical devices, we can reach this by tempering our costs with probability - rewarding corporate caution and penalizing poor communication. But for pharmaceuticals, we must represent the reality of the industry. A reality where it is those who walk on the knife’s edge for affordability who are cut the deepest by companies. A reality where the worst hurt are those forced to choose between their money or their life.

[1] Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty, ‘Product Recall: Managing The Impact Of The New Risk Landscape’, 2017, available at: https://www.agcs.allianz.com/news-and-insights/reports/product-recall.html

[2] Electrical Safety First, ‘Consumer Voices on Product Recall’, 2014, available at: https://www.electricalsafetyfirst.org.uk/media/1259/product-recall-report-2014.pdf

[3] FDA, ‘Recalls Background and Definitions’, available at: https://www.fda.gov/safety/industry-guidance-recalls/recalls-background-and-definitions

[4] US Government, ‘Code of Federal Regulations: Title 21’, Volume 8, Chapter 1.H, Section 810.A, available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-H/part-810

[5] US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, ‘Generic Competition and Drug Prices’, available at:

[6] R.Conrad & R. Lutter, ‘Generic Competition and Drug Prices: New Evidence Linking Greater Generic Competition and Lower Generic Drug Prices’, 2019, US FDA Report, available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/133509/download